For professionals

Diagnosis, classification, symptoms, and causes of hypersomnias

such as idiopathic hypersomnia, narcolepsy types 1 and 2, and Kleine-Levin syndrome

For professionals

such as idiopathic hypersomnia, narcolepsy types 1 and 2, and Kleine-Levin syndrome

Jump to page sections

According to the ICSD-3-TR, hypersomnias are a category of chronic neurologic sleep disorders that are also called central disorders of hypersomnolence (CDH). They cause people to sleep excessive amounts (long sleep), have excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), or both. EDS is a strong daytime sleepiness or need to sleep during the day, even with enough sleep the night before. These disorders are often debilitating, significantly affecting social, school, and occupational functioning. Symptoms and their severity may fluctuate.

Refer your patients to our web page “Read about hypersomnia sleep disorders.”

Hypersomnias may be classified as primary or secondary. Primary means it occurs on its own and isn’t caused by another condition. Secondary means it’s caused by or closely related to a different condition.

| Primary hypersomnias |

|

Idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) with and without long sleep |

|

Narcolepsy type 2 (NT2) without cataplexy |

| Narcolepsy type 1 (NT1) with cataplexy |

| Kleine-Levin syndrome (KLS) |

| Secondary hypersomnias |

|

Hypersomnia associated with a medical disorder, such as a head injury, a neurodegenerative disease such as Parkinson’s disease, or a neuromuscular disorder such as myotonic dystrophy |

|

Hypersomnia associated with a medicine or substance — although the ICSD-3-TR still labels this as hypersomnia “due to” a medicine or substance, the ICSD committee intended to change to “associated with” because it’s often impossible to be sure that a certain medicine or substance is the cause or is the only cause |

|

Insufficient sleep syndrome — sleepiness due to regularly not sleeping enough hours each night (7 to 9 hours for adults) |

|

Hypersomnia associated with a mental disorder, such as depression or seasonal affective disorder |

The average age of symptom onset is 16 to 21 years old. In addition to EDS, symptoms of IH may include:

The ICSD-3-TR diagnostic criteria don’t differentiate between IH with and without long sleep. The criteria are partly a diagnosis of exclusion because researchers don’t know the cause of IH or its biomarkers. The criteria are:

Note: The total 24-hour sleep time of 11 hours may need to be modified to account for cultural variability and stages of child development. For example, the cutoff needs to be longer in school-age children (age 6 to 13) who normally sleep 9 to 12 hours in 24. For an individual child, it’s also important to take into consideration changes from their historical normal.

Additional supporting features:

![]() Sometimes people who have significant symptom severity may not meet the full ICSD-3-TR diagnostic criteria for IH. If so, use clinical judgment to diagnose IH. Take great care to continue to rule out other conditions, and consider repeating sleep studies.

Sometimes people who have significant symptom severity may not meet the full ICSD-3-TR diagnostic criteria for IH. If so, use clinical judgment to diagnose IH. Take great care to continue to rule out other conditions, and consider repeating sleep studies.

The closest match to IH in the DSM-5-TR is hypersomnolence disorder. The diagnosis of hypersomnolence disorder requires the following:

Symptoms usually start during adolescence. In addition to EDS, symptoms of NT2 may include:

The ICSD-3-TR criteria are partly a diagnosis of exclusion because researchers don’t know the cause of NT2 or its biomarkers. The criteria are:

The usual age of symptom onset is 5 to 25 years old. In addition to EDS, symptoms of NT1 may include:

NT1 is caused by problems with central nervous system orexin signaling, which leads to REM sleep instability, including cataplexy. Therefore, the following criteria must be met:

Cataplexy is usually diagnosed based on history since people rarely have an episode during a doctor appointment, even if trying to trigger an episode. Home video footage may be helpful, so consider asking patients to try to film episodes.

Typical cataplexy is often critical for NT1 diagnosis because about 95% of people with it have low CSF orexin. It’s very important to differentiate typical cataplexy from atypical cataplexy and other mimics, as detailed below.

Watch this short BBC video of a cataplexy episode:

Episodes happen in specific parts of the body. It can be very subtle, sometimes lasting only a few seconds and only recognized by experienced observers such as the patient’s partner. When episodes are longer, there is bilateral loss of muscle tone in the face, neck, or legs, and sometimes also the arms. Examples include:

This is less common. Many parts of the body or sometimes the entire body are affected. It builds up over several seconds, usually starting as a partial episode in the face or neck, and may progress to complete weakness and collapse. Sometimes people may fall asleep during prolonged episodes.

Cataplexy usually lasts less than 2 minutes. It can last longer in these situations:

People who have typical cataplexy may sometimes also have these variations:

Atypical cataplexy is much less strongly associated with orexin deficiency and NT1 diagnosis. Episodes shouldn’t be considered typical cataplexy if 2 or more of these features are present:

Because sleepiness can present as inattention, impulsiveness, and/or hyperactivity, NT1 in children may be misdiagnosed as ADHD. Other conditions that NT1 can be misdiagnosed as include seizure disorder, schizophrenia, depression, autism spectrum disorder, insomnia, or obstructive sleep apnea. This can happen because of misinterpreting narcolepsy symptoms such as cataplexy, sleep-related hallucinations, social withdrawal due to sleepiness, or disrupted nighttime sleep. This is further complicated by the fact that these other conditions may be comorbid with narcolepsy.

Cataplexy in children:

Recognize Narcolepsy in Pediatric Patients: Detailed descriptions of symptom presentation, including cataplexy videos and screening and clinical interview tools

Symptoms usually start in early adolescence. KLS is defined by repeated episodes of severe excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep duration, with cognitive, psychiatric, and behavioral symptoms:

| In addition to excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep duration, symptoms of KLS during episodes include (at least one): |

| Confusion in time (and sometimes in space) |

| Slow speech |

| Derealization |

| Hyperphagia |

| Hypersexuality (usually in males) |

|

Other possible symptoms include: |

|

Childlike demeanor |

|

Hallucinations and delusions |

|

Headaches |

|

Hypersomnia associated with a mental disorder, such as depression or seasonal affective disorder |

The following criteria must be met:

Several long-term studies show an often-improving course, with episodes lessening in frequency, duration, and severity over the course of about 14 years. However, longer disease duration is predicted by:

Also known as menstrual-related KLS, use this diagnosis when hypersomnolence episodes only happen just before or during menses. These episodes:

Treatment with oral birth control pills may help.

For correct interpretation of overnight PSGs and MSLTs, recordings need to meet the following standard conditions:

Follow AASM guidelines:

For information specific for working with people who have hypersomnias, visit our guide for sleep study centers.

To meet these test protocols, you may need to help people access medical leave, such as FMLA or short-term disability, for a couple weeks from their work or school. This is especially the case for:

Refer your patients to our web pages:

Consider ordering HLA-DQB1 blood typing before doing a spinal tap to measure CSF orexin. If HLA-DQB1*06:02 is negative, CSF orexin will almost certainly be normal. In very rare cases, other rare HLA types are positive, and low orexin levels can happen (Miano, 2023).

Consider testing CSF orexin levels if the:

You should diagnose NT1 if the CSF orexin level is 110 pg/mL or less (using a Stanford reference sample) or less than one-third of mean values from normal subjects using the same test.

![]() In the U.S., you can get these tests by sending your samples to Mayo Clinic Labs:

In the U.S., you can get these tests by sending your samples to Mayo Clinic Labs:

For more information, visit Sleep Review Magazine’s article “Mayo Clinic Can Test Your Patients’ Orexin Levels.”

Recent studies show that IH with and without long sleep time should be considered as separate diagnoses:

Cluster analyses sort into the same group:

The only diagnostic criteria that distinguishes between IH and NT2 is that REM sleep in MSLT nap tests happens in NT2 but not in IH.

However, multiple studies have shown that if you repeat the MSLT:

People who are initially diagnosed with NT2 may eventually show cataplexy or low orexin levels. If this happens, change their diagnosis to NT1.

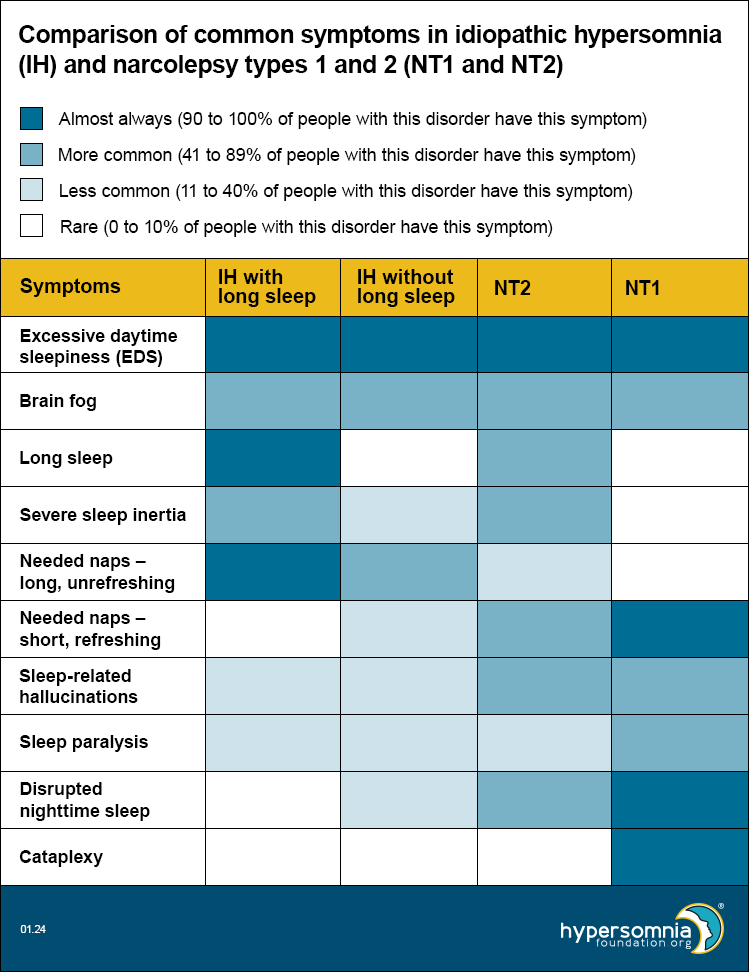

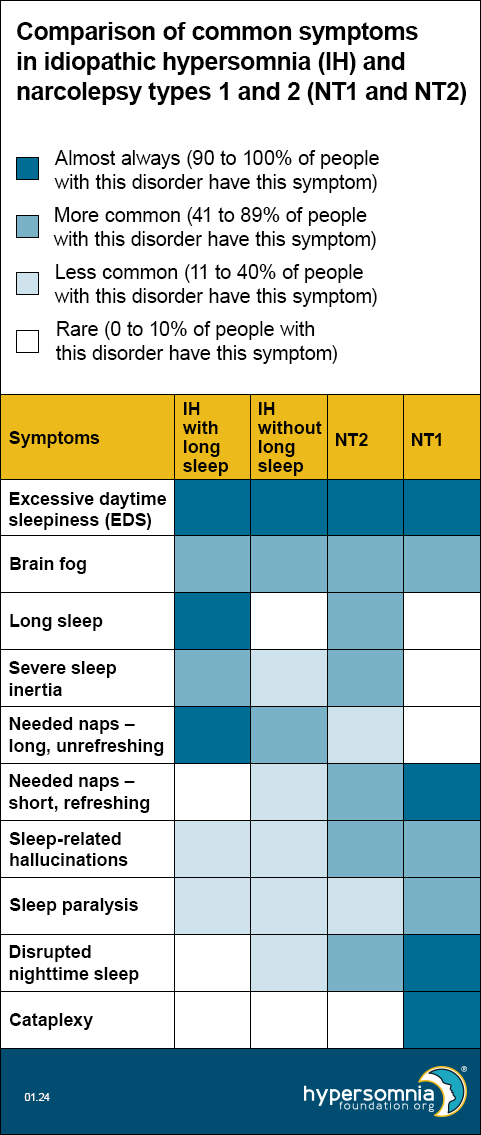

Each of these disorders causes EDS and brain fog. The table below shows how common the other symptoms are, depending on the type of sleep disorder. (Darker blue means a higher percentage of people have these symptoms.)

In 2020, European researchers published a proposal for new diagnostic criteria for central hypersomnias. Read our summary of this journal article, including a video by the primary author, Dr. Gert Jan Lammers, describing the difficulties of diagnosing hypersomnias and how the European proposal is designed to give a more inclusive and accurate system of diagnosis.

Although the diagnostic criteria for each of these requires that another disorder doesn’t better explain the symptoms, the presence of other disorders doesn’t rule out the hypersomnia diagnosis if EDS continues after adequate treatment of the other disorder. Also, if the hypersomnia predates the other disorder, the other disorder is more likely to be a comorbidity than a replacement for the hypersomnia diagnosis.

Sleep apnea is more common in people with hypersomnias than in the general population and may be the cause of hypersomnolence or comorbid with it. If sleep apnea is present, treat it as well as possible for at least 3 months before diagnosing a comorbid hypersomnia disorder.

Depression may be the cause of hypersomnolence or comorbid with it, but depression alone shouldn’t cause abnormal MSLT results.

Hypersomnolence in people with mental disorders is not necessarily caused by the mental disorder. For example, depression and ADHD are more common in people with hypersomnias than in the general population.

A person diagnosed with hypersomnia associated with depression must have both hypersomnolence and depression, and the two must be related. However, researchers don’t yet know whether the depression causes the hypersomnolence, the hypersomnolence causes the depression, or the two are related in some other way.

The same is true for ADHD. Read our journal article summary “ADHD Symptoms in Children with Narcolepsy.”

People with CFS have persistent or relapsing fatigue that doesn’t go away with sleep or rest. They clearly have fatigue rather than EDS, and they don’t have abnormal MSLTs or other problems with their sleep. CFS can be comorbid with a hypersomnia, but since fatigue can also be a symptom of hypersomnias, this can be hard to differentiate.

Read our article “IH, CFS and Fibromyalgia – How Do They Differ?”

About a third of childhood primary hypersomnias are associated with symptoms of significant autonomic dysfunction, such as orthostatic intolerance, palpitations, headache, and dizziness. These can be mistaken as symptoms of the primary sleep disorder.

These symptoms are recognizable at the time of presentation, but they may be masked once hypersomnia medicines are started. Therefore, screen at the initial presentation of the sleep disorder, using autonomic reflex screens and focused questioning. Read more in this 2021 study.

Adults with hypersomnias may also have increased rates of autonomic dysfunction, including POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome), that would benefit from early screening. Read our journal article summary.

Make this diagnosis instead of IH, NT1, or NT2 if you find that another medical condition is the primary cause of EDS. Hypersomnolence is associated with many conditions, including:

It’s especially important to consider these medical conditions when the hypersomnia diagnosis isn’t clear.

In these subtypes, although symptoms are due to a medical condition, the full criteria for NT1 or NT2 are also met. Therefore, the diagnosis is NT1 or NT2 associated with a medical condition (not hypersomnia associated with a medical condition). This can be very important for access to narcolepsy treatments.

Intermediate (110 to 200 pg/ml) CSF orexin levels have been found in some people with hypersomnolence and encephalopathies or immune-mediated demyelinating disorders. However, orexin levels are not always decreased in NT1 due to a medical condition, suggesting different etiologies.

Research in this area continues to evolve and affect classification.

The cause of IH isn’t known, and there may be different causes for different groups of people with it. People with IH have normal CSF orexin levels.

Studies have reported possible causes, including:

The cause of NT2 isn’t known, and there may be different causes for different groups of people with it.

NT1 is caused by problems with orexin signaling, most likely due to loss of hypothalamic orexin-producing neurons from an autoimmune process. T cell-mediated destruction of these neurons is most likely. The role of B cells and autoantibodies is unclear, so classical criteria for an autoimmune disorder are not all met.

Animal models show a causal relationship between orexin loss and narcolepsy.

Possible triggers include beta-hemolytic streptococcus and H1N1 influenza. However, neither causal associations nor mechanisms have been firmly established.

The cause of KLS isn’t known. However, studies suggest that a localized but multifocal encephalopathy occurs during episodes. The recurrent aspect and the adolescent onset (often occurring with an infection) suggests an autoimmune cause. There may also be circadian, genetic, or metabolic abnormalities.

Brain functional imaging is abnormal in most cases, showing:

Some studies have reported CSF orexin levels one third lower (but still in the normal range) during symptomatic versus asymptomatic periods. CSF cytology and protein are normal.

Risk factors include:

Visit our CME web page for more information.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed.; Text Revision; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2023.

Barateau, Lucie, et al. “Narcolepsy severity scale-2 and idiopathic hypersomnia severity scale to better quantify symptoms severity and consequences in narcolepsy type 2.” SLEEP, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsad323.

Billiard, Michel, and Karel Sonka. “Idiopathic hypersomnia.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, vol. 29, 2016, pp. 23–33, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.08.007.

Broughton, R., et al. “Ambulatory 24 Hour sleep-wake monitoring in narcolepsy-cataplexy compared to matched controls.” Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, vol. 70, no. 6, 1988, pp. 473–481, https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(88)90145-9.

Chervin, Ronald. “Approach to the patient with excessive daytime sleepiness.” UpToDate, 2023.

Chervin, Ronald. “Idiopathic hypersomnia.” UpToDate, 2022.

Cook, J.D., et al. “Identifying subtypes of hypersomnolence disorder: A clustering analysis.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 64, 2019, pp. 71–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2019.06.015.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: FITFH Edition, Text Revision: DSM-5-TR. American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022.

Fronczek, Rolf, and Gert Jan Lammers. “Narcolepsy type 1: Should we only target hypocretin receptor 2?” Clinical and Translational Neuroscience, vol. 7, no. 3, 2023, p. 28, https://doi.org/10.3390/ctn7030028.

Gool, Jari K., et al. “Data-driven phenotyping of central disorders of hypersomnolence with unsupervised clustering.” Neurology, vol. 98, no. 23, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000200519.

Jagadish, Spoorthi, et al. “Autonomic dysfunction in childhood hypersomnia disorders.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 78, 2021, pp. 43–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.11.040.

Kawai, Makoto, et al. “Narcolepsy in African Americans.” Sleep, vol. 38, no. 11, 2015, pp. 1673–1681, https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.5140.

Khan, Zeeshan, and Lynn Marie Trotti. “Central Disorders of hypersomnolence.” Chest, vol. 148, no. 1, 2015, pp. 262–273, https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-1304.

Krahn, Lois E., et al. “Recommended protocols for the multiple sleep latency test and maintenance of wakefulness test in adults: Guidance from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, vol. 17, no. 12, 2021, pp. 2489–2498, https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.9620.

Lammers, Gert Jan, et al. “Diagnosis of central disorders of hypersomnolence: A reappraisal by European experts.” Sleep Medicine Reviews, vol. 52, 2020, p. 101306, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101306.

Lecendreux, Michel, et al. “Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in pediatric narcolepsy: A cross-sectional study.” Sleep, vol. 38, no. 8, 2015, pp. 1285–1295, https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4910.

Luca, Gianina, et al. “Clinical, polysomnographic and genome‐wide association analyses of narcolepsy with cataplexy: A european narcolepsy network study.” Journal of Sleep Research, vol. 22, no. 5, 2013, pp. 482–495, https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12044.

Malhotra, Raman K. “Evaluating the sleepy and sleepless patient.” CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology, vol. 26, no. 4, 2020, pp. 871–889, https://doi.org/10.1212/con.0000000000000880.

Maness, Caroline, et al. “Systemic exertion intolerance disease/chronic fatigue syndrome is common in sleep centre patients with hypersomnolence: A retrospective pilot study.” Journal of Sleep Research, vol. 28, no. 3, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12689.

Maski, Kiran, et al. “Listening to the patient voice in narcolepsy: Diagnostic Delay, disease burden, and treatment efficacy.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, vol. 13, no. 03, 2017, pp. 419–425, https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6494.

Maski, Kiran. “Understanding racial differences in narcolepsy symptoms may improve diagnosis.” Sleep, vol. 38, no. 11, 2015, pp. 1663–1664, https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.5130.

Miano, Silvia, et al. “A series of 7 cases of patients with narcolepsy with hypocretin deficiency without the HLA DQB1*06:02 allele.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, vol. 19, no. 12, 2023, pp. 2053–2057, https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.10748.

Miglis, Mitchell G., et al. “Frequency and severity of autonomic symptoms in idiopathic hypersomnia.” Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, vol. 16, no. 5, 2020, pp. 749–756, https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.8344.

Murray, Brian James. “Excessive daytime sleepiness due to medical disorders and medications.” UpToDate, 2021.

Šonka, Karel, et al. “Narcolepsy with and without cataplexy, idiopathic hypersomnia with and without long sleep time: A cluster analysis.” Sleep Medicine, vol. 16, no. 2, 2015, pp. 225–231, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2014.09.016.

Trotti, Lynn Marie. “Central Disorders of hypersomnolence.” CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology, vol. 26, no. 4, 2020, pp. 890–907, https://doi.org/10.1212/con.0000000000000883.

Trotti, Lynn Marie. “Idiopathic hypersomnia.” Sleep Medicine Clinics, vol. 12, no. 3, 2017, pp. 331–344, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2017.03.009.

Vernet, Cyrille, and Isabelle Arnulf. “Narcolepsy with long sleep time: A specific entity?” Sleep, vol. 32, no. 9, 2009, pp. 1229–1235, https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/32.9.1229.

Zhang, Min, et al. “Narcolepsy with cataplexy: Does age at diagnosis change the clinical picture?” CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, vol. 26, no. 10, 2020, pp. 1092–1102, https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.13438.

Published Apr. 29, 2020 |

Revised Jan. 30, 2024

Complete update Jan. 22, 2024 |

Approved by our medical advisory board